John Test

ANGLICANS and

the CHURCH of ENGLAND

In Philadelphia

John Test was not a Quaker. That is to say, by the time he became an adult he was not a Quaker. His parents were Friends, i.e, Quakers and John Test as their child was probably a Friend.

I do not know when his parents became Quakers – this needs more research. John Test was not a birthright Quaker. He was not, in 1651 born to parents who were Quakers. Not until 1652 — upon climbing Pendle Hill in the Pennine range on the border of Lancastershire and Yorkshire George Fox experienced a vision: “the Lord let me see a–top of the hill in what places He had a great people to be gathered.” He went out from there and preached and won more and more followers. Later these followers became known as the Society of Friends.

In the record of his marriage he is listed as being of Christ Church London. This simply means that he lived in that parish. His wife, Elizabeth Sanders, is of St. Martin's in the Fields. Fire destroyed the records of the Anglican congregation in Philadelphia but in all likelihood John Test attended the Anglican Christ Church in Philadelphia. Later, his son John Test jr. is listed as a member of the Anglican congregation in Chester. John Test's name does appear from time to time in Quaker records but these instances are not definitive of membership. Once when a Quaker businessman owned him money he filed a complaint with the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting. But this merely shows that he was familiar with Quaker procedures and that the way to embarrass a Quaker was to file a complaint with the monthly meeting.

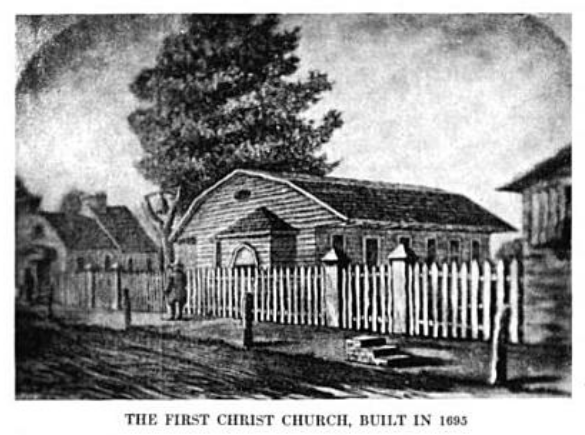

At first, there were but few non-Quakers in Philadelphia -- among them a few Lutheran Swedes and some Englishmen who belonged to the Church of England. It was not until 13 years after the founding of Philadelphia in 1695 that the latter petitioned the government for permission to create a parish. There were originally just 39 members.

Quoting H.M. Lippincott, though they lacked numbers “they made up [for it] in intelligence and in sustained hostility to the Quakers” (Early Philadelphia: its people, life and progress, pp. 68-69). With the building of the small Christ Church and later a College led by Dr. William Smith these Church of England men became a powerful party. They eventually absorbed the Lutheran Swedes into their membership as well as many of the Quaker followers of George Keith.

George Keith served as Quaker preacher achieving a measure of eminence. In defending Quakers from the accusation that their beliefs failed to conform to the basic tenets of Christianity, Keith wrote a declaration or confession of the beliefs of Quakers regarding various elementary principles of Christian orthodoxy.

Because of serious disagreement with other more politically powerful Quaker ministers over the nature of the faith, Keith left the Friends returning to the Church of England. When ministers of the Quarterly Meeting attempted to convince him to amend his views, he reportedly said, that there were “more damnable heresies and doctrines of devils among the Quakers than among any profession of Protestants.” The politically powerful Quakers viewed Keith as a radical dissident who trampled “the judgment of the Meeting under his feet as dirt.”

The Anglicans rejected the Quaker dominance in this new colony. Here in Philadelphia the Anglicans were the politically weak minority dissidents. To them it must have seemed the world had turned upside down. It was natural to them to see the faith of The Church of England established by law. It was illegal to offend or criticize the Quakers in Philadelphia. This policy offended the Anglicans sufficiently to cause them to send complaints to the home government asking that the colony be taken from the Quakers and turned into a royal province.

“Settlers from before the Quaker immigration and recent arrivals complemented Keithian [Keith was a former Quaker who became an Anglican deacon and a leader of the anti-Quaker forces] energy with wealth and leadership. A quarter of the Anglicans arrived in Pennsylvania before 1690 and over two-thirds before 1700. A number of them, such as John Test, Walter Martin, and Jonas Sandelands, had been in Pennsylvania before 1683. Such experienced men provided a talented core of vestrymen. ...In ability and experience, they matched Quaker leaders like Andrew Job, John Sharples, and Hugh Roberts.”

Barry Levy, Quakers and the American Family: British Settlement in the

Delaware Valley (Oxford Univ. Press, 1988), p. 163.

References:

Charles P. Keith,

Chronicles of Pennsylvania from the English Revolution to the Faiz-la-Ct

1688-1748 to the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle

Julia B. Leisenring & Patricia A. S., ForbesGuide to Christ Church, Philadelphia (Christ Church Philadelphia, 1984).

Marla Maples Dunn and Richard S. Dunn, The Founding 1681-1701 in Russell Frank Weigley, Nicholas B. Wainwright, Edwin Wolf, Philadelphia: a 300 year history.

Deborah Mathias Gough, Christ Church, Philadelphia: the nation's church in a changing city s(Philadelphia: Univ. of Penn. Press, 1995).

digitally designed by Igino Marini.

See his web page: on the history of Fell types.

The flowers used in the horizontal lines are Fell Flowers.

The title is in another Fell Font -- GreatPrimer.