Is John Test the Villain of the Witch Trial?

John Test, as the prosecutor in the Philadelphia witch trial, may well be the villain of the proceeding. As the sheriff of Philadelphia in the 12th month of 1783 and as the chief law enforcement officer he reviewed the evidence, filed the complaint and, at least, assisted in the prosecution of two women, Margaret Mattson and Yeshro Hendrickson, accused of witchcraft. So on the face of it, John Test clearly appears as the villain.

John Test prosecuted the case. He brought the case to the Grand Jury when, we may assume, he could have simply held that there was not sufficient evidence to prosecute or that it was simply absurd to believe in the existence of witches.

Of course, we will never know whether John Test relished prosecuting these women or found it disgusting. The motives for prosecution may have been complex. Perhaps community reactions to the women were intensifying requiring intervention to calm things down.

It seems clear that a case was made that these women, at least, Margaret Mattson's behavior was disagreeable and bothersome. Evidence provided to the grand jury convinced them that a trial was warranted. Witnesses, whether willing or not, whether hostile to the prosecution or hostile to the defendants, did appear in court. That some of the available witnesses did not appear is also telling.

The purpose of the trial may not have been to convict these women but to cause them to modify their behavior. If Margaret Mattson was amenable to persuasion, the trial and the decision of the court should have modified her behavior. Perhaps this was the whole point of the investigation and trial.

I suspect that Penn and his Council had no intention to convict these women of witchcraft. Their aim was to calm the situation and return the community to functioning normally.

English Law

But the ordinary people appear to attribute Mattson's behavior to witchcraft. These two women were not just bothersome. The best explanation, at least for the ordinary uneducated person, is that they are bothersome because they were witches.

The chief driver here is English law -- according to English law, witchcraft was illegal. William Penn and the colony of Pennsylvania had to remain vigilant to avoid violating British law so egregiously that Penn lost control of his colony. Losing control was always a threat.

With British law in mind, John Test may well have felt that he lacked the authority to simply ignore the accusations against these women. Witchcraft was a serious matter in 17th century England.

Witchcraft was taken seriously

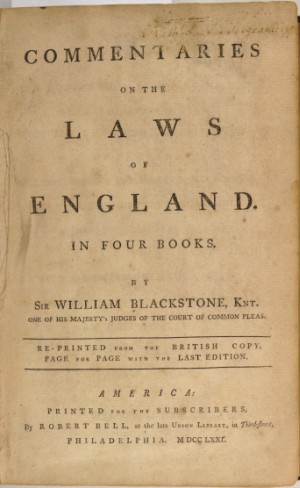

Even many years later, the eminent British jurist William Blackstone (1723 –1780), whose Commentaries on the Laws of England are regarded by United States Courts as the definitive pre-Revolutionary source of common law, wrote:

To deny the possibility, nay actual existence of witchcraft and sorcery, is at once flatly to contradict the revealed word of God, in various passages both of the old and new testament: and the thing itself is a truth to which every nation in the world hath in it's turn borne testimony, either by examples seemingly well attested, or by prohibitory laws....

Commentaries on the Laws of England, Vol. 4 p. 60

In Britain, questioning the existence of witches amounted to heresy. Under William Penn's rule in Pennsylvania it probably amounted to good sense. We do know that neither William Penn's nor John Test's views on witchcraft or the quality of the evidence led either of them to dismiss the case.

Three levels of review

Before this case went to trial three layers of review occurred. John Test examined the case, Penn and his Council examined it and the Grand Jury examined it. Unfortunately, the Grand Jury of twenty–one of the leading businessmen of Philadelphia ratified proceeding against the pair of alleged witches.

It is interesting that John Simcock, a neighbor of Mattson's who held 2200 acres in Ridley Township where both Mattson and Henrickson lived served on Penn's Council. Simcock was present on the 7th day of the 12th month when the Council examined the case against the two alleged witches. The Council referred the case to the Grand Jury. Simcock was absent from the Council on the day of the trial.

The Grand Jury presented a true bill believing they heard sufficient evidence from the prosecutor to believe Margaret Mattson and Yeshro Hendrickson probably committed a crime and should stand trial for their offenses.

The Alleged Witches’ Peculiar behavior

Clearly these women caused annoyance in their community. Their behavior was peculiar and their neighbors reacted to it. Various accounts say that they engaged in Finnish folk remedies. Perhaps their cures were mistaken as witchcraft.

Several of her neighbors testified against Mattson. The fact that no one testified on their behalf should not be counted against them since British legal procedures did not ordinarily permit the accused to present a defense against the charges.

Pennsylvania Law

There was no law against witchcraft in Pennsylvania. So the prosecutor must have been assuming that British law applied in this case. Under British law witchcraft was punishable by death. The only crime in Pennsylvania that carried the death penalty was for willfull murder. What would Penn have done if Margaret Mattson had been found guilty? What sort of punishment would she have received? These questions have no definite answers.

Even today people believe in witches. Recent polls indicate that from 20%-25% of the American population believe in witches. The most prominent believer in witches is Sarah Palin the 2008 Repubican candidate for Vice–President. John Test probably believed in the existence of witches. So did the majority of those on the Grand Jury.

Possibly the neighbors of Mattson and Henrickson believed they were witches and they brought their complaints to John Test. Perhaps John Test rode down to Ridley Creek where Margaret and Nils Mattson lived and interviewed some of the neighbors. Maybe he thought that by prosecuting the case and by a jury reviewing the evidence (and finding the accused women innocent) that it would put an end to the disruption. Perhaps the goal was to frighten the women enough to induce them to change their (disruptive) behavior.

We will never know. One thing is clear: this trial would not have occurred without William Penn's consent to let it proceed. Penn could have told John Test to drop the case. At any point he could have thrown the case out. Penn must have seen something that validated holding a Grand Jury inquiry and a trial. There must have been something, some point, some purpose that led these men to believe the situation warranted a trial. No transcript of the trial was ever recorded. The record of the trial gives us nothing but the essential details:

1) Two women: Margaret Mattson and Yeshro Hendrickson were indicted by a jury composed of 21 men.

2) The record of the actual trial refers only to Margaret Mattson. We learn nothing about Yeshro Hendrickson.

3) Henry Drystreet testified that he was told 20 years ago that the prisoner, viz., Mattson, was witch and that she bewitched several cows. He testified further that James Saunderling's mother told him that she bewitched a cow but afterwards said she was mistaken.

4) Charles Ashcom testified that

2005 Gallup Poll: 21% of American's Believe in Witches

December 15, 2009 – A new Harris Pol 23% of Americans believe in witches

A History of Delaware County, Pennsylvania, and Its People, Volume 1 By John Woolf Jordan